How to Be Creative: Lessons in Doodles

If I’m honest, not every student in my art classes wants to be there–sometimes art is just an elective that needs to be filled, and they have no choice.

Knowing this, I attempt to make each lesson fun as possible. But sometimes fun isn’t enough to keep students engaged in . . . oh, let’s say, a perspective lesson or a cross-hatching composition using value scale.

If I’m honest, not every student in my art classes wants to be there–sometimes art is just an elective that needs to be filled, and they have no choice.

Knowing this, I attempt to make each lesson fun as possible. But sometimes fun isn’t enough to keep students engaged in . . . oh, let’s say, a perspective lesson or a cross-hatching composition using value scale.

So, occasionally, I’ll announce to the class: “Today, I do not want you to care about what you create. Just create whatever.”

Why? Because to be creative, the brain needs to feel free to do so. No rules. No timeframes. No grades. Let the creative beast out of its cage and see what it does instinctively.

And as an art teacher, I want to teach more than just skills and drills. I want you to learn creativity.

Easier said than done, you might say; and yes, it is. I mean, how do you ‘just create’ anyway?

I will refer to this enigmatic quote from Picasso:

“To draw, you must close your eyes and sing.”

This infers that to draw—or create—shut out what you see in the objective world and let that ‘mysterious something that is uniquely YOU’ deep within the soul well up and flow out like a song.

Why a SONG? A song is a musical or rhythmic vocal utterance. Heart, mind, and soul collaborate to produce something from within. To sing your song can take some bravery because you are baring the innermost you . . . unless you are a very young child who still has no concept that the innermost you might be rejected, judged, or mocked by your peers. Kids just release it. And then giggle.

So, here’s the challenge: let out the innermost you.

Close your eyes to eliminate any distractions, insecurities, or comparisons.

What's deep down there?

Let THAT out.

ON paper.

A weird thing happens to us as we progress from our tiny worlds full of indulgent creativity—we learn that maybe what we can’t create. Or it's silly and has no value, or . . . it would reveal too much of who we are.

To which I say, no holding back. Release those pent-up emotions, burdens, whatever—let in out in line, shape, and color.

Why, you may ask? Even if you are not an artist, this non-verbal expression can be relaxing, grounding, and meditative.

So without needing to employ any skills, a fun way to do this is by doodling. We sometimes do this absent-mindedly on the phone, in a meeting, or at school, so why not intentionally?

If you are a teacher or homeschool parent, these are fun exercises to use as games, warm-ups, or even as an art lesson.

Supplies you could use:

Crayons, pastels, colored pencils, watercolor paint, sharpies, or colored ink pens. Try using a variety of them together as mixed media.

But, if all you have is a pencil or ballpoint pen–just use that.

Let’s begin . . .

Simply doodle. Grab a sheet of paper and start. This may seem awkward if you are older, so give yourself a moment to get used to it. If the student is younger than age 6, this will be easy. Try not to think, let intuition take over, and give your brain a time-out.

Now, let's get your eyes out of the way. Young kids love this, older ones not so much—close your eyes and doodle. Try imagining a favorite food, vacation spot, or movie. Maybe try focusing on a specific emotion, memory, or event. When you do this, see what happens on the paper.

Listen to music. Move your pencil to the rhythm or beat. I like to play Classical, Jazz, Lofi, or something without lyrics—again, try to avoid concrete thoughts.

Just Doodle . . . again. Do you see a difference? This time your doodles may look looser. You may feel more comfortable letting your hand move along the paper without the brain interfering. NOW look for PATTERNS or images in the doodles and color them in.

Turn your doodle into a Miro. (watch a Miro composition come together here!)

Try combining a few elements from each doodle exercise into a deliberate, planned composition—similar to the work of Spanish artist Joan Miro. His paintings were abstract, playful compositions full of shapes, lines, and primary colors. Look at your doodles. Choose the most interesting shapes, lines, and colors which you automatically created on paper. Now, take 5 of them and create a purposeful composition. Stack them, spread them out, whatever you think looks good to YOU. Not to anyone else.

Try these out with your kids or students—of any age!

Young children simply have fun while building fine motor skills.

Older students discover new ways to create compositions and loosen their creativity.

And, hey, if you are an adult, it’s a relaxing way to unload any daily stressors.

Next time we’ll get more deliberate with our shapes and lines. Cubism and Gesture drawing on its way . . .

Wander, play, imagine–

***Ever wonder what your doodles mean? Check out my free infographic here.

How to Be Creative: Think Like a 4-Year-Old

When my son was 4, he painted this piece of abstract art and titled it:

Eating Something.

I thought it was brilliant. (As any parent of a 4-year-old would think.)

If I could guess, my son wasn’t deliberately creating art. . . he was just having fun with finger paint— maybe, that was the brilliant part.

When my son was 4, he painted this piece of abstract art and titled it:

Eating Something

I thought it was brilliant. (As any parent of a 4-year-old would think.)

If I could guess, my son wasn’t deliberately creating art. . . he was just having fun with finger paint— maybe, that was the brilliant part.

He was having fun.

And he created something.

If you are a teacher, parent, or grandparent of young children, you’ve seen plenty of these uninhibited and swiftly created art pieces.

Chances are, your 4-year-old self created some too.

These early manifestations of pre-K imagination are joyful to observe. One of the reasons is that they are spontaneous, and as adults, we do not trust spontaneity so well. We have trained ourselves out of it.

But, back to Eating Something.

How did my 4-year-old son decide that this messy blur of paint strokes would best depict Eating Something? Perhaps the swirling, confusing lines he made felt like eating something. Eating what, though? Spaghetti and blueberries? Or, maybe he was painting the slurping sounds of eating. Or the mess left behind on his napkin. Who knows.

The point is a 4-year-old naturally creates.

Children don’t need to LEARN to use their imagination; they just DO. And, what’s more impressive. . . they usually LOVE what they create. Maybe, on a good day, I love 50% of what I make while the rest gets crumpled and tossed because my adult brain just got in the way.

I love this quote from Picasso:

“All children are artists. The problem is how to remain one once we grow up.”

Tragically, somewhere along the educational journey, we slowly ‘unlearn’ creativity. We begin to worry if it’s done correctly. Or wonder if anyone will like it. We lose the courageous 4-year-old artist's brain and replace it with a careful one.

So HOW do we stop this from happening?

Creativity comes from an uninhibited desire or willingness to depict something unique from one's imagination. This is all fine and good, but . . . how do we turn on that ‘imagination hose’ when we need to water the seeds on a blank piece of paper or a canvas?

Here’s a discovery I’ve made: sometimes, the simple act of ‘creating anything’ can turn on the faucet to be creative.

As a teacher, one of the best exercises I have found to help the creative mind roam free is DOODLING.

Yep, doodling. Scribbling. Automatic drawing. Call it what you like; it’s the foundation of any 4-year-old’s art masterpiece.

It may sound simple, but the intuitive act of creating random flows of lines, patterns of shapes, and swatches of color frees the artist’s brain to move in abstract and inventive directions. Think of it like searching for figures in the clouds— look long enough, and eventually, you’ll SEE something.

Some very famous master artists of the 20th century were known for what I like to call, ‘master doodling’. I mean, really—some abstract art looks a lot like well-planned, intentional, gestural, colorful . . . doodles.

Just look at a Kandinsky painting, for example:

Composition in Yellow by Wassily Kandinsky

He was able to “see music” and “hear color.” If you knew nothing about Wassily Kandinsky and stood before one of his paintings full of roaming colors, dancing lines, and complex geometric patterns on one canvas, you might think, “That’s some serious doodling right there.” But once you are told, “No, no–it’s a painting of a musical composition,” you just may look long enough and declare, “I see it! I SEE music”.

I mean, that’s creative. And, of course, ground-breaking for an artist of the early 20th century.

I could also claim it’s the same type of abstract creativity employed by my 4-year-old son in ‘Eating Something.’ One work of art is an invention of a skilled master who found a way to depict a conceptual performance as a picture. The other is by a 4-year-old who intuitively depicted an ordinary, everyday activity as a picture.

It would seem that the 4-year-old and the master are inexplicably connected.

Here’s another bit of insight from Picasso:

“It took me years to paint like Raphael but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

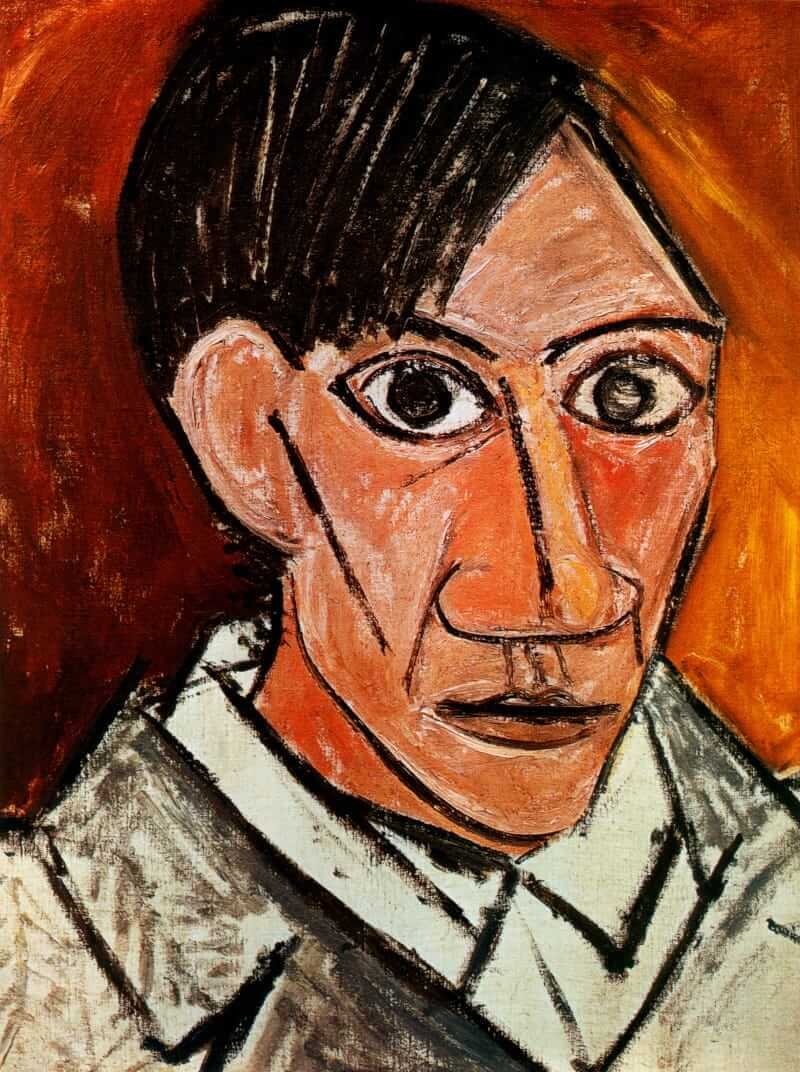

Just look at this early self-portrait by Picasso:

Picasso Self-Portrait 15 years old (1896)

Masterful. Also literal—by that I mean you can identify the features of the face as realistic, even though the strokes and colors are painterly.

Now let’s look at what Picasso mastered 10 years later:

Picasso Self-Portrait 25 years old (1907)

Another self-portrait, but this one is more childlike in its use of aggressive lines, odd proportions, and abstract color. It bares the soul of the artist and most likely the way he viewed himself in the world. Instead of portraying himself realistically, Picasso portrayed an idea of himself—as a child would. The child does not have the skills to paint realistically; Picasso had the skills but chose to capture something raw and primitive instead.

Love or hate it, Picasso created a new way of viewing a subject. He was able to regain fearless childhood creativity.

So, back to the question: How do we stop ‘unlearning’ creativity?

Try DOODLING.

Young artists will be good at this; older ones may need a bit of encouragement to break loose.

Here are a few tips:

Kick logic to the door.

Allow your drawing hand to move fluidly, even quickly, anywhere on the page.

Use the entire paper. Don’t try to draw small; go BIG.

Don’t let your brain nag you into ‘making the lines make something.’

Use any type of lines; smooth, straight, jagged, bumpy; let your mood decide what they will look like.

Look for ‘shapes in the ‘clouds’--do you see anything interesting in those lines? Try coloring in any patterns you find interesting.

Don’t overthink it. Don’t try to be clever. Don’t worry about who will see it.

Maybe even give it a title. Like ‘Eating Something.’

Have fun.

Create something.

It doesn’t have to be brilliant . . . but who knows, it just might be.

For more fun doodle exercises and lessons, check out Being Creative: Doodle Drawing.